Abstract

Due to the accelerating developments of globalization, digital information and communication technologies… the nature, mission, and academic identity of higher education have been changed. As a result, a new form of higher education has emerged. That is “transnational higher education (TNHE)”. However, in addition to the direct influence of info – global advances on TNHE, additional internal factors such as economic and academic concerns are interring the scene, governing consequently with other factors, the goals, processes, resources, and directions which TNHE is apt to pursue. Moreover, TNHE is facing as any forming science, several challenges related to: incongruent missions and / or priorities, problem of accreditation, insufficient resources, inappropriate methods of teaching and learning, mismanagement, lenient governance and regulations, and biased attitudes.

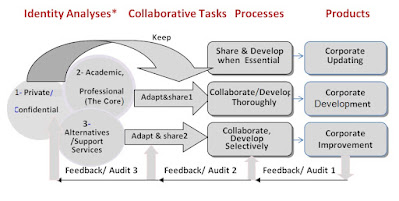

To counteract above shortcomings and contributing to the advancement of TNHE , this article is introducing two working principles: inter-independence and collaboration. And then produced two operational mechanisms: the first, a strategic inter-independence collaborative model by which each TNHE partner could achieve its academic and professional needs, and the second, a quality audit / evaluation framework that could help each TNHE institution focusing on achieving its priority goals.

Key Terms: Transnational Higher Education, Inter-independence, Collaboration, Inter-independence Collaboration, Inter-independence Collaborative Strategies, Inter-independence Collaboration Model, Information Age, Globalization.

Introduction

Man, who had limited his schooling from the era of Plato to needs within confined borders on earth, had entered by the mid-nineties of the twentieth century the cyberspace age. As a result, the psycho-social, economic, physical and educational means and priorities for a productive schooling seem to have changed. The reason beyond this shift in schooling priorities stems from the fact that the cognitive as well as the behavioral fields in which man operates have extended to infinity (Hamdan1987).

Information and communication technologies (ICT) are altering who we are, how we think, what we believe, and how we behave. The human race is in essence developing a new humanity. By digital ICT means, it becomes possible to communicate, interact, and learn- receive information instantly (Hamdan2007; Papp and Alberts1997; Stewart1997; Kupfer1997). ICTs are enabling humans and institutions to go cyber space, thus changing profoundly many facets of doing things, including the ways of Transnational Higher Education TNHE (International Research Center 2006; Kok 2006; O’Donoghue and Others 2000).

Globalizing ICTs, have caused a massive flow of information and innovation throughout the globe. They, the two together are seen by this Writer, to represent a decisive operational factor of current TNHE. In fact, the streaming of human resources, programs, skills, expertise, academic and professional exchange across the world, indicate the decisive role of Globalizing ICTs for the advancement of TNHE (Answers Corporation1997; Burbules and Torres 2000; Cogburn 2012; UNESCO2007).

It follows therefore, that continuing schooling within restricted classroom walls or specific school or local borders means simply gearing priorities of educational system backward to outdated conventional knowledge, preparing generations at best to live the persisting past, since isolated educational institutions can’t empower learners to develop themselves for living the open Space Age as much as to be attached to memories, folklores and obsolete epistemology (Hamdan1992).

Further, While institutions could keep their individual identities, academic integrity and the independence of in-house decision making, they could at the same time initiate new interactive relationships that are professional, equitable, productive, and responsive to institutional needs. These intents and processes resemble what this writer calls here inter-independence collaboration.

Transnational Higher Education Based Inter-independence Collaboration- A New science of eLearning is in the making

Transnational (cross-border) Higher Education “TNHE” is generally practiced in three forms: student /academic mobility, program mobility, and institution mobility (Naidoo 2006 in Yi Cao2011).

TNHE came strongly to the fore of educational scene twenty years ago due to the pressures of globalization and constant demands of info technologies and knowledge economy that urged international States to launch a series of educational plans since the mid-1990s, to:

– create new valuable markets by expanding education into new geographies.

– promote reform and quality of TNHE,

– boost Global academic rankings,

– get economic revenue by globalizing the business of higher education,

– be recognized as exporters of higher education research and services (KPMG International Cooperative2012; Mok,2009):.

In fact, expanding direct governmental backing and financial support to foreign higher education institutions in forms of tax deduction benefits, educational grants and land concessions, are expected to reinforce more collaborative transnational initiatives and as well encouraging civic society gurus to empower universities to address sustainable development challenges of the twenty-first century (Koehn 2012).

To achieve optimized consequences of these info-global factors and to neutralize their possible negative side effects, TNHE institutions need to adopt two operational principles: the first is inter-independence which enables them individually and as joint venture groups to interact with a sense of responsibility toward one another, and the second is collaboration which allows each partner to maintain equitable agreed upon needs.

For TNHE as recognized a new schooling trend has transformed the concept and practice of local isolated higher education institutions to global collaborating learning- teaching networks in which “learners are located in a country different from the one where the awarding institution is based” (Vignoli 2004).

Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Australia, and UAE, among others, are notable cases in which the states have explicitly declared intentions to make their territories regional hubs of such new type of education. Thus leading to dramatic developments of today’s TNHE as part of the states’ coping strategies (Ka Ho Mok 2009). In fact, “One in five TNHE branch campuses in the world is hosted by the UAE”, and China doubled student enrollment from five million post-secondary students in mid-1990s to more than 34 million in 2010 (Koehn 2012).

Consequently, TNHE institutions are established with no apparent limitations; special governance laws are introduced; distinctive methods of learning, instruction, assessment, human and professional communication techniques are formed and practiced; TNHE graduate study programs are offered; new terms such as: transnational education, “glocals”, eStudent, education mobility, and internationalization were coined; specific types of literature and research have emerged; and specialized forums and conferences are convened (Choudaha2012; Connelly and Others 2010; Coverdale-Jones 2012; Drew and Others 2008; Naidoo2009; Mok 2009; Ong and Chan 2012;The University of Nottingham 2013; Wilkins and Balakrishnan 2013; Yonezawa2009; Yoshino 2004).. hence, a new educational science: Transnational Education, is borne

However, TNHE as any newly forming science, and in lieu of its highly compelling pace of developments, is facing several technical and practical problems; and understanding of its real status on the ground is still incomprehensible due to lacking of systematic study statistics (Naidoo 2009).New and more detailed governance and regulatory regimes for steering the growing number of TNE providers and programs are still urgently needed.

For example, the Sino-UK TNE partnership was initiated without specific organizing formula but personal connections. Thus, a need was observed to work out a precise form of partnership and its associated financial implications for both parties, while cultural diversities and differences in educational tradition, curriculum challenges, communication style and organizational practices are among factors affecting the operation of a TNE partnership over time. Changes in macro-economic factors such as exchange rate can also lead to termination of a TNE project ( Zhuang 2009; Wenying2007)

Quality Assurance issues to regulate effectively TNHE, to ensure its quality, to promote mutual recognition of academic / professional degrees or qualifications, have all become the concern of governments and international organizations. More work is evidently needed to improve current external quality assurance systems in regard of quality audit, professional accreditation and mutual recognition of academic and professional attributes (Social Science Paper 2012). The last part of this paper is dealing with issue.

Moreover, economic preference in terms of generating revenue over other human and academic merits that determine the cause of collaborating TNHE institutions, has added immensely to its persisting problems. Hence, it is essentially expected from TNHE providers to adopt strategies which ultimately differ from the business model to reflect the intrinsic value of higher education whose main goal is to serve the human cause (Altbach 2010).

The Concepts and Roles of inter-independence and collaboration in TNHE

To negate above shortcomings or at least to ease their negative effects on TNHE institutions, two philosophical organizational principles are proposed for partnership: inter-independence and collaboration.

The concept of inter-independence was firstly coined by this Writer in a work published in Arabic at 1987 and then in English at 1992.With inter-independence, the organization may appear more aware of its strengths, limits and needs and those of others. it is expected while maintaining a highly integrative own profile and mutually exclusive identity, tends without apparent reservations to share own qualities and shortcomings for the sake of achieving better independence which is free of dismay, threat, or uncertainty.

Working with the concept of inter-independence is expected to maintain an educational process by which every organization can maintain equitable relations with others, and explore its uniqueness then develop it and share it without the sense of being hopeless or the risk of being overtaken, subdued, or offended by others.

Collaboration on another hand, is a behavioral paradigm, and a well-defined relationship performed by two or more higher education institutions (or individuals) to achieve mutual strategic goals (ETC- Education Transition Choices1997).

For collaboration to succeed however, it calls for a relationship built upon commitments to: the concept of mutual relationships and goals, a sense of shared ownership, jointly developed tasks and joint responsibilities, mutual authority and accountability for success, and sharing of resources and rewards (Bishop1993).

Further, a real feeling of mutual trust among partners of TNHE should be available to motivate working together without too many risks. THE collaborating institutions by utilizing the philosophy, working principles and techniques of inter-independence, will help them in neutralizing emerging risks and balancing them against academic and professional vulnerabilities (Ruohomaa and Kutvonen 2008).

Proposed Systemic strategic Model for Inter-independence Collaboration of TNHE TNHE has conventionally handled issues of students’ learning and academic programs. It is strongly advocated by this Writer however, that the mission of Inter-independence collaboration of TNHE institutions should be extended to all other factors and processes, since educational institutions are in reality Gestalt operating systems built upon “inputs- processes- outputs”. Hence, students’ learning and academic programs are not operating in isolation of other components of the TNHE system. Rather, they are affecting and being affected by all factors within the system.

Thus, TNHE institutions, in order to be effectively responsive in their inter-independence collaboration strategies and succeeding consequently in their learning – teaching missions, are required to customize, transform, or develop their human, academic, professional, educational, psychological, physical, regulatory laws, and other support services, whenever deciding to initiate the transnational collaborated efforts. Needless to indicate that without this Gestalt systemic operational approach, TNHE may turn into a “trial- error” risky endeavor, failing students as well institutions whenever any shortcoming may emerge.

The strategic Systemic Model of Inter-independence Collaboration is depicted in the following diagram.

Figure

1: A Proposed Strategic Systemic Model for Inter-independence

Collaboration in Transnational Higher Education (developed by

Author)