Children’s readiness for school learning develops throughout the early childhood years, beginning from birth and continuing through the age of three, when they enter kindergarten. This continues through the age of six, when they begin their first primary school education, continuing through the age of twelve, when children begin intermediate school education in middle school, and finally, through the age of fifteen, when they begin high school.

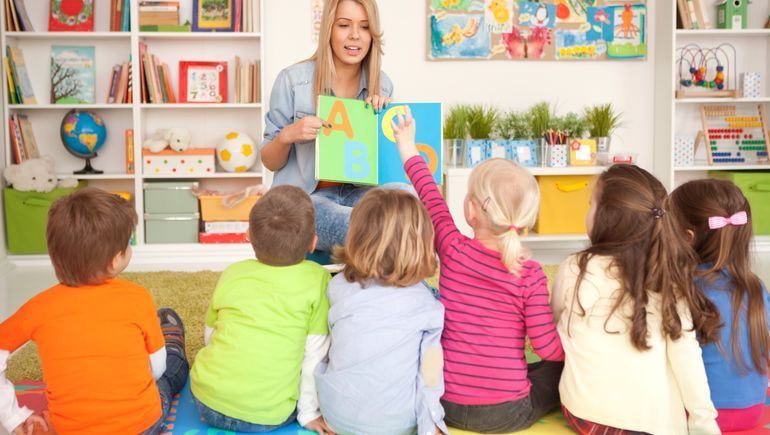

The most important type of readiness for children’s personal development and shaping their future is readiness for kindergarten: the first school where children begin their formal education outside of the informal family environment. Children’s readiness for kindergarten and their successful fulfillment of the simple requirements of this learning together form the first fundamental building block in building their personalities and establishing the kind of future they will have in adulthood.

Children appear prepared for kindergarten education due to their regular and continuous exposure to emotionally stable adult family members; a rich, safe, and non-emergent physical home environment; activities familiar to the children and repeated daily; peers who are healthy in their personalities and habits; materials, equipment, and environmental conditions that stimulate curiosity and sensory and cognitive enjoyment of working within them; and a sense of success in interacting with them and learning what they need from them.

The most important behavioral indicators by which families initially identify children’s readiness to begin kindergarten or subsequent school stages are: clear self-confidence and curiosity; cognitive alertness; attention to what is happening around them; realism in dealing with people and things; understanding the needs of family members and peers and cooperating with them in daily activities and situations; self-discipline; and the ability to communicate and interact with others within the family environment.

While children’s cognitive and behavioral achievement across their lifespan in the family and the previous school stage is an indicator of their readiness or lack thereof to learn in kindergarten or the subsequent school stages: elementary, middle, and high school… families and teachers obtain information regarding the extent of children’s readiness to learn from four sources:

1- The dynamics and interactions of the classroom or family environment, and how children behave and the responses of family members and teachers within these environments.

2- The bilateral relationships between family members and teachers on the one hand, and the children learning on the other. If these relationships are effective, interactive, and regular, they positively indicate the children’s readiness to learn at the relevant school level.

3- The children’s achievement results in the previous school level. Communication skills, language, reading, mathematics, classroom behavior, sensory perception and attention, social interaction with others, and the scarcity or absence of behavioral problems among children, all indicate, when positive, their readiness for school learning, or for transfer to higher grades if necessary when they excel.

4- Family information regarding the children’s motherhood and the family’s social environment: complete, separated, divorced, or broken; the ethnic origins of the mother and father; the educational level of the family members in general; and the type and amount of economic income.

It is worth noting a general conclusion here: the more complete, sufficient, and positive the information from the four sources above is, the more it indicates, in principle, the children’s readiness to learn in the relevant grade or school stage. However, if information conflicts from one source to another, or is partially or completely missing from one or more sources, then the decision by the family or teachers regarding the children’s readiness to learn is inappropriate in most cases. That is, the lack or weakness of their readiness for the required learning becomes clear, and as a result, the causes and shortcomings require immediate treatment.

Factors Influencing Children’s Learning

Many factors influence or interfere with learning, which we summarize with clarification into two categories: factors specific to the children themselves, and then environmental factors specific to the external environment. These can be referred to as the children’s internal environmental factors (i.e., their physical and psychophysiological environment) and the external environmental factors surrounding them, such as family, school, and society.

Internal and Psychophysiological Factors. The most important of these factors are the following:

1- The Genetic Factor.

It is now generally agreed upon in psychology that children inherit approximately 70% of their personalities, body structures, and psychological characteristics from their ancestors, including their parents and grandparents. The remaining 30% is normally nurtured by the environment in their personalities through processes of formation, enrichment, deletion, and addition through upbringing.

The genetic factor controls every characteristic of children’s personalities, from eye color, height, general build, and skin color, to brain cells and endurance. Even many human feelings, emotions, and psychological problems, which until recently scientists attributed to the environment, are now being traced back to specific brain cells or specific genetic factors. For example, depression, which many believe results from environmental stress or despair in dealing with it, has recently been identified by physiological psychologists as a specific gene (SIRT). When children experience increased frequency, their likelihood of developing depression increases (The Open Program and The World of Science, Radio London, March 17, 1996).

2- The maturation factor, or the stage of development experienced by children.

This factor determines the type and nature of learning and their ability to achieve it. Children between the ages of birth and two learn motorically, between the ages of 3 and 6 learn sensory-realistic, and between the ages of 7 and 12 learn sensory-logically. By the age of 13 or older, they become capable of learning symbolic concepts, abstract theoretical knowledge, and experiences (see various references to developmental psychology, especially by the Swiss scientist Jean Piaget). The type, degree, and speed of maturation or growth vary from one individual to another, primarily based on genetic predisposition, and then on the extent to which the environment is effective in modifying or accelerating it.

3- The Intelligence Factor. Intelligence

which appears to be largely hereditary, controls the type and speed of learning. The relationship between intelligence and learning in normal circumstances, between children and their environment, is directly proportional: the higher the intelligence, the higher their learning ability.

The type of learning that children are capable of or can excel at, is directly related to what is called special intelligence, special abilities intelligence, or aptitude. Whatever the case, intelligence is linked to the psychological concept of cognition: the basis of human intelligence and the vessel for learning. All of these—cognition, intelligence, and learning—are functionally governed by the health and integrity of brain cells and regions, 75% of whose psychophysiological properties are due to the genetic factor we discussed earlier.

4- Motivation and Human Incentives.

Motivation is a latent psychological force that drives children to perform a specific task. Whether we’re talking about curriculum responsibilities, experiences, or knowledge essential for children’s success in school or everyday life, motivation motivates them to accomplish such tasks through learning.

Motivations are linked to human inclinations and desires. Here, incentives appear to be factors that positively stimulate learning, or they can be repulsive or repellent, causing children to avoid learning. Incentives can be strong, active, or dynamic, moving children from one learning activity to another in a never-ending process. Alternatively, they can be weak and empty, leaving children unable to act or learn. They appear inactive and sluggish, prone to abandoning learning at the earliest opportunity.

Incentives, according to their source, fall into two categories: internal, intrinsic, and possessed by children, which automatically direct their focus and movement from one learning activity to the next. Their individual accomplishments, along with their personal ambition and relentless desire to achieve, serve as an incentive to engage in further learning. External incentives are those stemming from, directed, and governed by the environment, verbally through terms of encouragement, praise, and titles; symbolically through medals, responsibilities, and literary roles assigned to children; or materially, such as gifts and presents of various types and forms.

The most powerful types of human incentives for learning are those that originate within children (intrinsic), powerful and effective in their continuous stimulation of their desires or enthusiasm to move from one learning responsibility to the next. I don’t believe the weakness of young people in developing countries in achieving, their general neglect or indifference to learning, and their tendency to drop out and sometimes resist it (except through the supervision of family, teachers, school counselors, and others) are the result of two factors related to human motivation: the low strength of their intrinsic motivation, which is incapable of motivating them to initiate and continue the required learning, and their primary reliance in their daily activities on external environmental incentives.

In this regard, it is noticeable that families and teachers see their students learning or pretending to learn. If the family and school encourage them with words, titles, roles, or gifts, they actually move toward learning. However, if they do nothing, they appear inactive and lack motivation, and learning appears weak and problematic in developing countries!

Unfortunately, the diseases of motivation have spread, as has been observed, to workers and employees in both the public and private sectors (sometimes), resulting in widespread neglect, laxity, and corruption to an extreme, sometimes unbearable degree. Learners will remain behind in their learning, and developing societies will continue their cultural slumber, as long as they continue to rely on external stimuli and their intrinsic motivations remain empty or ineffective.

5- Prior Acquisition. Acquisition is the sum of knowledge, experiences, inclinations, values, and skills that result from learning. Learning and acquisition—as we mentioned earlier—are twins: when one occurs, the other is assumed to occur. Acquisition, under normal circumstances, leads to a cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reservoir in the brain and human inputs, from which children draw—when abundant—to succeed or excel in their daily tasks.

Acquisition, as prior learning, facilitates children’s assimilation of new learning. How? Because they use it as axes, rules, or sources upon which relationships are established that connect new learning stimuli to appropriate behavioral responses (according to behavioral theory in general); or as cognitive balancing processes and the subsequent assimilation, transformation, and modification of cognitive layers, as in Piaget’s theory; Or as triggers of insight or inspiration that enable children to perceive learning, as in Gestalt theory; or finally, as “cognitive beacons” that guide encoded neural impulses through their specialized codes (symbols) to their locations in short- and long-term memory, leading to consolidation and interaction, and consequently, new learning, according to Hamdan’s theory of psychology in his book “Learning Theories and Methods,” 2015.

Previous learning, which is the result of prior learning, usually leads to new learning that children seek. If this learning is diverse and rich, new learning appears rapid and superior by most standards. However, if prior learning is weak, incomplete, or nonexistent, new learning becomes difficult or sometimes impossible.

External Environmental Factors:

Although learning stimuli can occur independently, as children reflect on their experiences and knowledge and emerge with new learning in the form of knowledge, skills, or emotions, the environment under normal circumstances constitutes an unlimited source of learning stimuli and the primary source for stimulating and implementing learning in children.

Environmental factors are numerous and varied, beginning with the family and the family environment; the school with its teachers, peers, and curricula; and extending to the wider community: the street separating the school from the family; various shops and public institutions; the media, which relentlessly broadcasts its stimuli 24 hours a day; social customs or the general culture of the community; the economic situation, the level of civilization; the geographical nature of the environment; and its general climate.

All of these factors, and others we have not mentioned due to space limitations, interfere with learning, either negatively or positively, to the extent that each one is negative or positive. An authoritarian, lax, or disintegrated family, a dilapidated school, negligent or professionally incompetent teachers, deviant peers, incomplete or unavailable educational curricula, a streetscape characterized by its defeatist appearance and immoral behavior, selfish or cheap media messages, social tolerance for the use of prohibited substances such as drugs, deteriorating economic capabilities, a climate that is too hot and humid or too cold without air conditioning or even regular electricity to protect the soul and body from extreme physiological cold or heat, or from darkness, illiteracy, and general environmental ignorance or cultural backwardness—all serve to undoubtedly hinder learning psychologically, administratively, and materially.

The result? Children shift from actively learning to advance personally and socially in the future to learning to survive in the best or most capable circumstances.